Doug Moe writes about Clara Colby in the Madison Magazine.

Just about everyone knows of Susan B. Anthony, while almost nobody knows about Clara Colby.

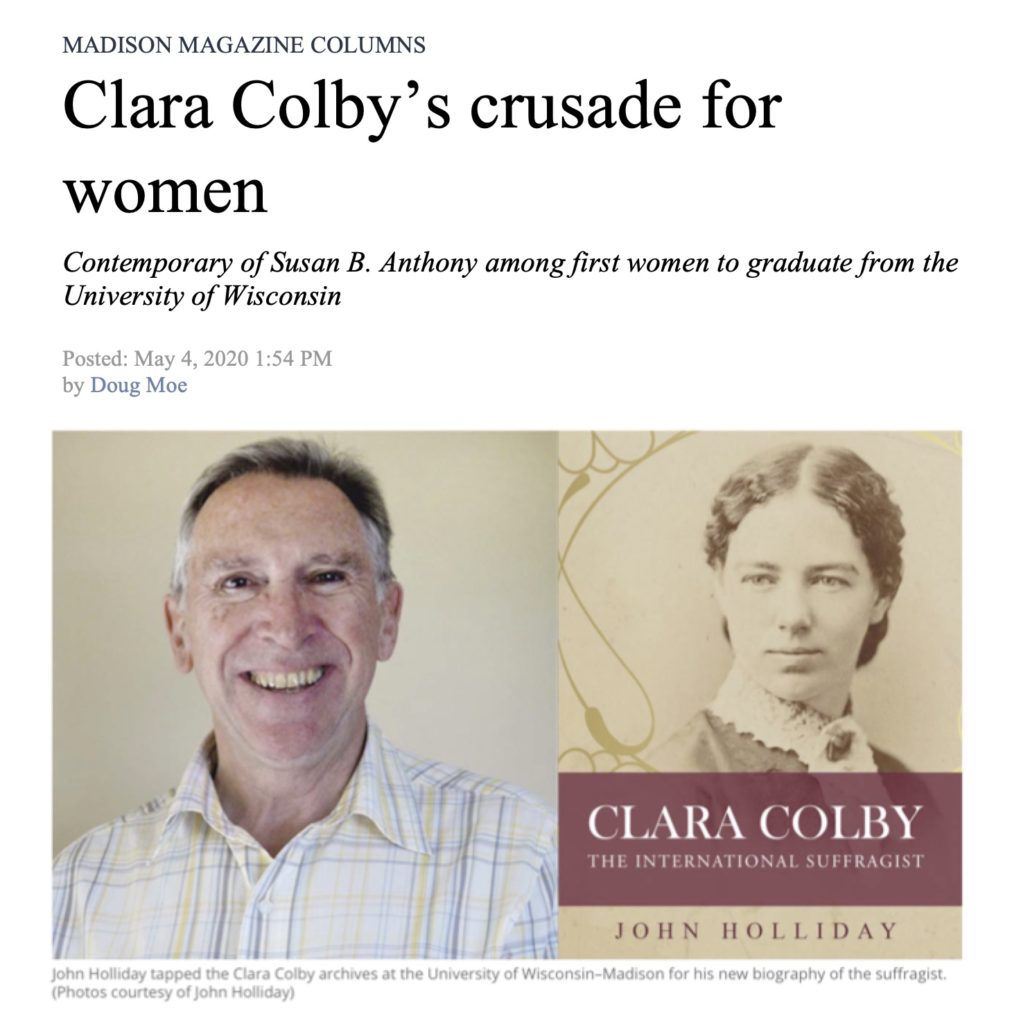

John Holliday is trying to change that, and he came to Madison to do it.

Anthony, of course, was a leading advocate for gender and racial equality in the United States in the second half of the 19th century. Her efforts — perhaps most notably in support of a woman’s right to vote — were recognized decades later when her image was used on a U.S. one-dollar coin.

And Clara Colby?

Colby (1846-1916) was a dynamic speaker and compelling writer on women’s issues. Anthony called her the best writer in the women’s movement, a sentiment shared by Anthony’s famous colleague, Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

In a 1888 letter to Colby praising an issue of Colby’s newspaper, The Woman’s Tribune, Stanton wrote, “I have just read it through, every word from beginning to end, and have thoroughly enjoyed its courageous tone, its radical thought and its evident determination to go to the root of the evils that block woman’s path to freedom.”

Clara Colby grew up just outside of Madison and attended the University of Wisconsin, one of six women in the first class of female graduates in 1869, and its valedictorian.

For John Holliday — whose biography “Clara Colby: The International Suffragist” was recently published — Colby’s archive, housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison, was invaluable.

Holliday, who grew up in England, is a businessman and author of an earlier book, “Mission to China: How an Englishman Brought the West to the Orient,” a biography of the missionary Walter Medhurst, best known for translating the Bible into Chinese.

Medhurst was Holliday’s great-great-grandfather. In researching Medhurst, Holliday learned a bit of Clara Colby’s story: her grandmother was Medhurst’s sister. (Which means Holliday is distantly related to Colby, second cousin twice removed.)

For all that genealogy, it was the singular, stirring aspects of Colby’s story that got his attention. At home in Australia, he’d share it with friends, saying he was considering a book on Colby.

One woman said, “You have to do it! You’ve got a wife, two daughters and a granddaughter. You owe it to them all.”

“She persuaded me to have a go at it,” Holliday told me last week, by phone from his home in Queensland.

The task initially appeared daunting. Colby had lived in many places: Madison, Nebraska, Washington, D.C., Oregon.

“I thought her records would be everywhere,” Holliday said. “But when I called the librarian in Beatrice, Neb., she said, ‘Oh, no, all the files have been collected in Madison.’”

Holliday came to Madison in September 2018 and immersed himself in Clara Bewick Colby’s life.

The Bewick family emigrated from England in 1849 and settled on a farm in Windsor, just north of Madison.

Clara eventually enrolled at UW. Her valedictorian speech in 1869 — she’d studied to be a teacher — urged her classmates to “face sternly against wrong in every shape; in devoting yourself to the service of others.”

Holliday notes that the first class of women almost didn’t graduate: University President Paul A. Chadbourne opposed co-education and “threatened to withhold their degrees on the basis they had followed the regular men’s curriculum rather than that of the university’s ‘Female College.’ He relented, however.”

Chadbourne even offered her a teaching position, but at less pay than men in the same post. Early on, she wrote a letter pointing out the inequity.

“They told her,” Holliday said, “that if she didn’t like it, she could leave.”

She did, taking a teaching job in Fort Atkinson.

She also, in 1871, married an aspiring lawyer named Leonard Colby, “a dashing young fellow,” in Holliday’s estimation but also one of questionable character. “She suffered a lot because of him. He was quite a rogue.”

They moved to Nebraska, where Leonard practiced law and Clara, in time, began publishing The Woman’s Tribune, a monthly newspaper devoted to women’s issues.

What’s infuriating — even for a man, reading Holliday’s book all these years later — is how dismissive and condescending the men of Colby’s time were.

A Nebraska newspaper editorialized: “Mrs. Colby is considering the scheme of starting a newspaper for the advancement of women’s suffrage …. Our parental advice to all about to enter the ranks of journalism is, ‘Don’t monkey-with the buzz-saw, and give it lots of room.’”

The Woman’s Tribune lasted 26 years.

After a Colby speech to a women’s suffrage convention, another Nebraska newspaper opined: “It is our private opinion, publicly expressed, that when a wife and mother leaves her home, her husband and her children to travel over the country lecturing on women’s rights or any other subject, she has departed from that sphere for which God and nature designed her, and has left vacant the place that no other can fill — the home.”

In fact, it was Leonard, Colby’s husband, who was more frequently absent, and their subsequent divorce damaged — confoundingly, when viewed today — Colby’s standing in the women’s movement.

“Some of the women were prejudiced regarding divorce,” Holliday said. “After that she was never asked to speak at the national conventions, and before that I think she spoke at every one.”

Still, Colby never relinquished the fight. She traveled to England, speaking on women’s suffrage, and was present in 1911 when 40,000 women marched in London for the right to vote.

Clara Colby was 70 when she died of pneumonia in September 1916 at her sister’s home in California. Her ashes were sent to Wisconsin and are buried at Windsor Congregational Cemetery.

This year is the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution becoming law, which gave women the right to vote. Thirty-six states needed to ratify it for that to happen, and they did. Wisconsin was first.